- Exclusive

- The People Report

- 5 min read

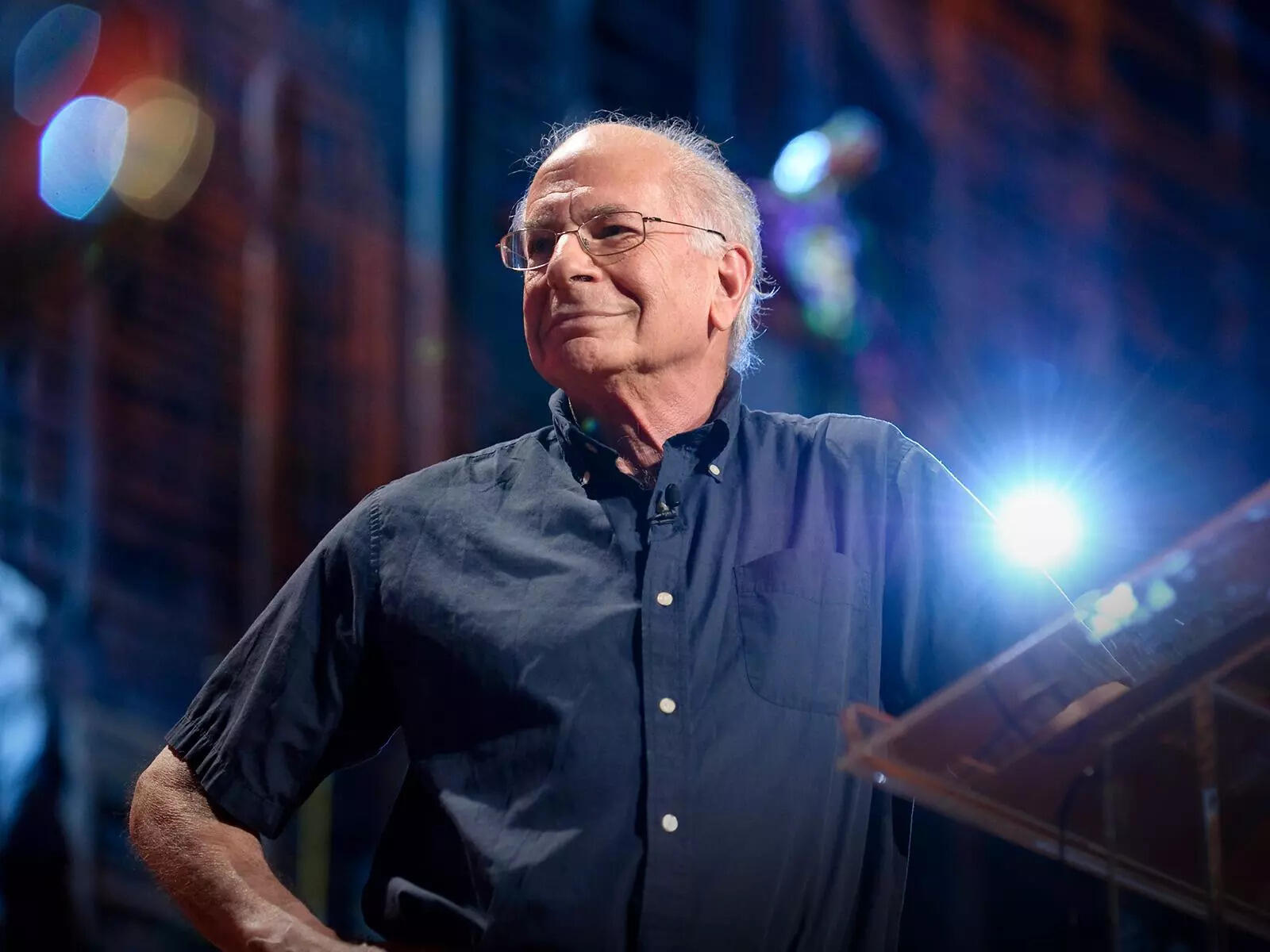

Daniel Kahneman: a tribute to the ‘brand’ psychologist

Daniel Kahneman demonstrated how we abandon logic and leap to conclusions. To him, human rationality was like a sand castle on a beach, washed away in the very next tide of impulse, bias, presumption, or delusion. Dr. Kahneman saw himself as a psychologist more than an economist, says the author in his tribute to the legendary Israeli-American author and psychologist who passed away recently at the age of 90.

Rarely does a body of work impact diverse disciplines as profoundly as his rich contribution. He created an entirely new discipline of behavioural economics that immediately applied to every field of human behaviour from brand building to politics. He demonstrated how we abandon logic and leap to conclusions. To him, human rationality was like a sand castle on a beach, washed away in the very next tide of impulse, bias, presumption or delusion.

Dr. Kahneman saw himself as a psychologist more than an economist and with that perspective he did research that shredded the very plausible construct of the “homo economicus,” the “economic man” a rational being acting from self interest and doing things objectively. Risk, loss, gain, bias, intuition, euphoria and conviction were all within his domain.

He was asking and answering some very essential and profound questions: Do we truly think? Do we understand probability intuitively? Can a statistical model devoid of noise always beat a human decision model? Dr.Kahneman’s research was elaborative on ‘heuristics’ or the mental shortcuts and he found that people rely on intellectual hacks that often lead to impulsive, emotional and ‘incorrect’ decisions that go against their own best interest.

These misguided decisions occur because we form judgements too soon and once so formed, go along with them to our own detriment. In his words “humans are much too influenced by recent events and they are much too quick to jump to conclusions under some conditions and, under other conditions, they are much too slow to change.”

Hence, his ask was for humans to ‘delay intuition’. Dr. Kahneman was teaching at Princeton university when he shared the 2002 Nobel memorial prize in Economic Sciences “for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgement and decision-making under uncertainty.” He found that confidence beats competence and we are all prone to place too much faith in our inner voice. Much of this he simplified for all in his 2011 book “Thinking, fast and Slow.”

Dr. Kahneman spent much of his career working alongside psychologist Amos Tversky, who he said deserved much of the credit for their prize-winning work. Tversky died in 1996. The application of psychological insights to the study of economic decision-making is in a way a never ending project. There are no universal laws here like say, in the Physical sciences. Man is very much a creature of habit. Our senses compel our mind. Our heart rules our brain.

Dr. Kahneman defined two modes of thought: System 1, in which the mind acts quickly, relies on intuition, immediate impressions, and emotional reactions; and System 2, in which the mind, slows down, functions more rationally and analytically. Per his findings, we are all governed by the System 1 toolbox: rules of thumb, cognitive biases, and speed of judgement. Hence hardwired reflex beats true thinking.

Dr. Kahneman and Tversky did experiments that demonstrated various cognitive biases such as anchoring, loss aversion, confirmation etc but their most famous postulation is the framing effect. Kahneman - in his later years-- studied the difference between what is “experienced” and what is “remembered”. And he came up with the “peak-end rule.”

According to the rule, if we have a pleasurable experience at the end of conversation, for example, we tend to remember the entire interaction fondly. If we have a bad experience during check in at a hotel, we end up looking for all else that is displeasing, and sure enough find plenty. Similarly, if we experience less pain at the end of a medical procedure, we recall the entire experience as less painful. The remembered experience is more important than the experience itself. This is a deep insight into how we perceive the world.

As a psychologist he bombed the most value generating pursuit in the world - investing-- and he explained investors to themselves. His guidance can indeed minimise fees, losses and regrets. Behavioural economics interrogated the impulse of risk amongst investors. Why do we sell our winners too soon and hold the losers for far too long? Why are hot streaks not just seen as luck? If risk is a part of the game, then why is there manic when the market falls? Do we ignore the odds even when we know they’re against us? Losses are twice as painful as gains are pleasant. This triggers a vastly irrational behaviour in all of us. All of us --data savvy investors most of all - don’t incorporate all available information. Often people extrapolate the future from almost no data at all. He said “Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.” Therefore we think short streaks in a random process enable us to predict what comes next.

He showed us a mirror when his experiments proved people can’t make out equal propositions framed differently. When he asked people if they want to take a risk with an 80% chance of success, most say yes. Asked instead if they’d incur the same risk with a 20% chance of failure, the answer was negative. He picked on small instances - menu listings in English that list calories to the right, after the item name and description have less impact on calorie conscious eaters than those that list the same calorific information to the left, before the name and description. He said, “The most important question to ask before making a decision is, ‘what is the base rate?’” He meant you should begin every major decision by figuring out the objective odds of success, given the historical range of outcomes in similar situations. He urged everyone -- investor, career seeker, voter and consumer to “ask why”.

Instead of assuming that the status quo is valid, one takeaway is that we must not be resolute. We must be fickle. Intelligence means the ability to change your mind; when the evidence justifies it. Have no sunk costs and embrace errors of thought and judgement. “All of us would be better investors,” he often said, “if we just made fewer decisions.” A light has gone away from this world though his work has made him immortal. Thank you Dr Kahneman.

COMMENTS

All Comments

By commenting, you agree to the Prohibited Content Policy

PostBy commenting, you agree to the Prohibited Content Policy

PostFind this Comment Offensive?

Choose your reason below and click on the submit button. This will alert our moderators to take actions